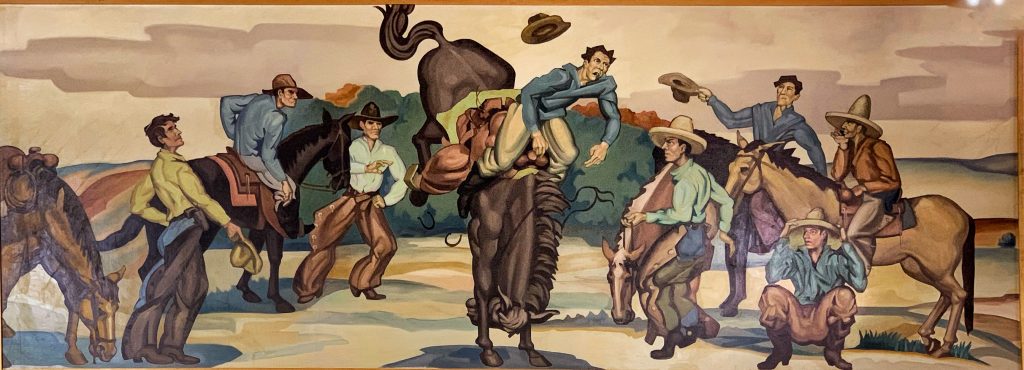

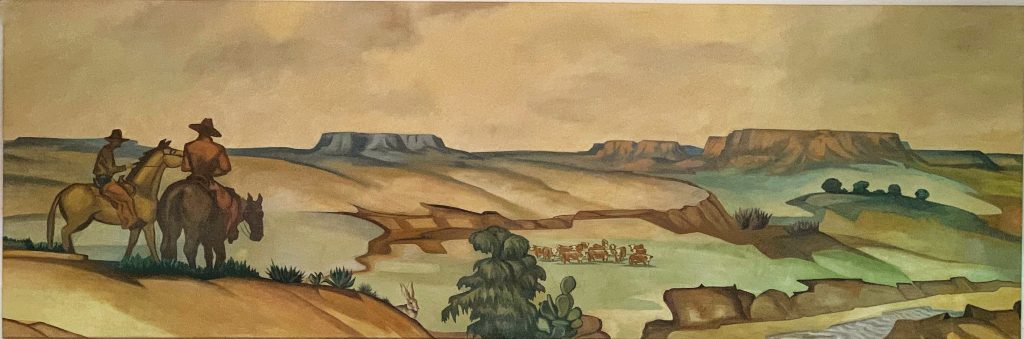

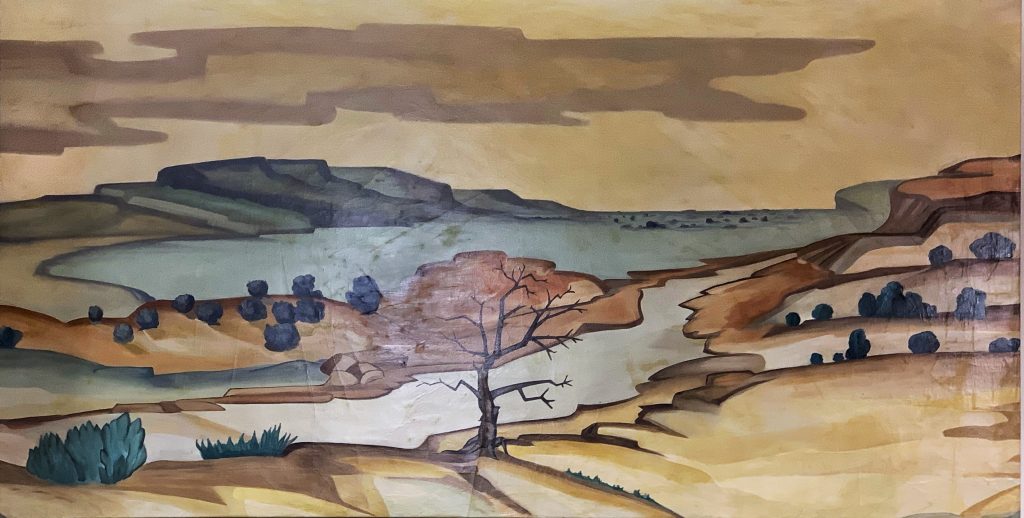

3 sections of A History of Ranching mural now hanging in Texas State University

“Indiana” Schmidt and the Lost Mural

2001 Dorey Schmidt, Ph.D.

One day in the early 1990s, Dorey Schmidt visited Four Winns Ranch during a Wimberley Civic Club Home Tour. Fascinated with the cultural treasure represented by James Buchanan “Buck” Winn’s studio, and dismayed by the inappropriate obscurity of his work, Schmidt hit upon the idea of creating a “TexKit,” a sort of mobile, hands-on educational exhibit pioneered by the Institute of Texan Cultures.

Schmidt drew up plans for a “WinnKit,” presented them for the approval of the Wimberley Institute of Cultures board, and then applied for a grant from the Texas Committee for the Humanities. Using funds from that grant, Schmidt wrote the script, assembled photographs, reproductions, and artifacts into a cedar presentation trunk hand-crafted by her husband, Robert Schmidt, a wood artisan. Using the WinnKit, she told the story of Buck Winn’s artistic and architectural genius to local civic organizations and hundreds of Wimberley schoolchildren. For many, seeing the WinnKit in action was their first introduction to his work. Other docents continued those presentations for a number of years.

It was during the process of researching for the WinnKit that Schmidt stumbled on the first clues to the “Lost Mural.” Pinned to the huge working wall of Winn’s studio were several sections of a cartoon (preliminary sketch) for a very large mural with a Western theme, containing cowboys and cattle and other depictions of early ranching days. Sorting through 35 mm slides, Schmidt found a picture of what was obviously part of the finished mural, installed in a room with a rail fence and wooden tables and chairs. Questioning old friends and family members, she learned that the mural had been a commission for the hospitality room of a brewery in San Antonio in the early 1950s.

One section of the Buck Winn Mural, “A History of Ranching” on Display at the Wimberley Community Center.

Over the years, as banks and public buildings were remodeled or razed, a number of Buck Winn’s major works were lost or destroyed—installations like the wonderful murals in the Medical Arts Building in Dallas, and the magnificent gold-leaf bas-relief of the “History of Flight” at Amon Carter Airport in Fort Worth, and other works of art whose only remaining record is a photograph or sketch. As an art historian, Schmidt wanted to find out what had happened to the mural at the brewery. Did it still exist? Or was it another piece of Buck Winn’s art that was lost forever?

Again consulting local acquaintances, she learned that the brewery was the Pearl Brewery, a venerable Texas brand of beer whose San Antonio plant had been sold to Olympia, a brewing company headquartered in the Northwest. The hospitality room, which was housed in the huge oval structure that had once been the horse barn, was only being used for company and private functions, and was no longer open to the public. Even more ominous was the news that the Corral Room had been remodeled in the early 1970s, and was now adorned in gilt and red velvet as the Lillie Langtry Room!

One section of the Buck Winn Mural, “A History of Ranching” on Display at the Wimberley Community Center.

But, donning her “Indiana Jones” explorer’s hat, Schmidt was determined to find out which list the mural was on—the list of the lost—or the list of the rediscovered. She called the brewery, seeking information. No one knew. After all, the remodel had taken place more than twenty years past, and many of the new executives were from out-of-state and knew little of the brewery’s history.

One day as Schmidt pleaded on the phone for some kind of information, any clue as to what had happened to the mural, Mr. Jack Kratz, the vice-president of marketing, finally said, “I’m sorry that I don’t know anything about the Buck Winn mural, but I just remembered . . . there was a man who once worked here as manager of the hospitality room. He’s retired now, but he might know something.” Aha! Schmidt was encouraged. From her faculty office at UT-Pan American in the Rio Grande Valley, she called the number she’d been given. Mr. Chuck Remling answered the phone. “Mr. Remling, this is Dr. Dorey Schmidt. I understand that you once worked for Pearl Brewery, and that’s where I obtained your number. I’d like to ask you some questions, if I may?” “Well, I guess I can do that,” was the answer. “They told me you were the manager of the Corral Room, is that right?” “Yes, I worked there fourteen years.” “And you were there when it was remodeled?” “Yes.” “Great!” Schmidt quickly got to the point. “Mr. Remling, do you remember what happened to the Buck Winn mural that was on the wall?” There was a brief silence on the other end of the phone line. “Who wants to know?” BINGO! Getting warmer! Schmidt identified herself again and told him why she was asking these questions. Then the whole story came out:

“I always liked that mural, and when they were remodeling and took it down, they were just going to throw it in the dumpster. But I thought that it might have some historic value—or at the very least, there were a couple of panels that I thought I could cut out and frame for my house (his listener shuddered), so I took the rolls of canvas and put them on top of some cabinets in a storage room. I kind of forgot about them, and later, when I retired, I don’t know what happened to them. I guess they could still be there.”

One section of the Buck Winn Mural, “A History of Ranching” on Display at the Wimberley Community Center.

Within minutes, Schmidt was back on the phone with the brewery V-P, describing the location of the storage shed. Within the hour, he called back. “We’ve got your pictures. What do you want us to do with them?” Weak with relief that the mural still existed, Schmidt explained that she was prepared to enter into negotiations with the brewery to arrange a possible donation of this valuable art work so that it could be brought home to Wimberley, where it was created. The V-P’s next comment stunned her. “When do you want to come get it?” Her answer to that was swift. “Tomorrow!” No need to give him time to change his mind!

Schmidt frantically phoned the rest of the Winn committee and told them to get a rental truck. She called Southwest Texas State University Library to arrange for climate-controlled storage of the huge (280 feet long) mural. Contacting a local museum for guidelines, she prepared a draft of a gift agreement which would legalize the acquisition. And the next day she drove up from the Rio Grande Valley to San Antonio, while Julie Harrison, Dodie Spencer and Robert Schmidt drove down from Wimberley to meet her at the Pearl Brewery.

They rendezvoused at the brewery, where the rolls of canvas were stacked neatly on the asphalt floor of a shed. A couple of workers stood by to load the rolls. Mr. Kratz signaled them to unroll a portion to be sure it was the right painting, and as they did, one of the workers grabbed a straw broom to remove some of the twenty years of dust. The combined screams of the women persuaded him that was not the thing to do! The rolls were loaded into the rental truck, and the triumphant entourage drove away. Buck Winn’s lost mural, “The History of Ranching,” had been found.

But the story doesn’t end there. The mural was examined, and was in remarkable condition for having been stored for over twenty years in an unheated, uncooled shed under the broiling Texas sun. But Buck Winn often used house paint on his murals, and in this case that turned out to have been a wise choice. WIC made plans for restoration, but it was going to be very expensive for the more than 2,000 square feet (200 m2) of canvas. Just one fifteen-foot section would cost $7500 to be repaired and restored by a conservator.

About that time, Dr. Schmidt was invited to give a lecture at the Delaware Art Museum in Wilmington. During her PhD. internship there, Schmidt had become acquainted with Helen Sloan, the widow of famous “Ashcan School” artist John Sloan. Now Helen was living in a retirement home, and Schmidt went to visit. There she told the story of the lost mural, thinking that it would entertain her elderly friend.

At the end of the account, Helen Sloan asked, “Is your organization a non-profit group?” When Schmidt responded, “Yes,” Helen continued, “You know, the John and Helen Sloan Art Foundation provides seed money for groups who are working on arts projects. I would like to send your group something to help.”

Schmidt thanked her for her generosity and returned home, telling the WIC Board that the organization might even get $500 from that one story-telling session. Within a few weeks, however, when a letter from the Sloan Foundation arrived in the WIC mailbox, the check enclosed was for $5000! Local contributions made up the rest, and the work on the mural restoration began.

So the generosity of an East Coast art foundation actually provided the funds for restoring this first section of the Buck Winn “History of Ranching” mural. This section is on display at the Wimberley Visitor Center, pending the completion of Wimberley’s Community Center, which is set for April 1, 2006.

One section of the Buck Winn Mural, “A History of Ranching” on Display at the Wimberley Community Center.

Although the original Winn Committee had hoped that the entire mural could be returned to Wimberley and reassembled, interest from private collectors and the need for additional restoration funds led to the sale of some sections when another WIC committee, headed by Pete Anderson and Al Sander, took charge of the mural. Through their efforts, another section was restored and is displayed in the main entry hall of Wimberley High School.

Through gift and purchase, the Southwest Writers Collection of the Alkek Library at Texas State University (formerly Southwest Texas State University) now owns some eighty feet of the mural which will be restored and installed on permanent display in the main lobby of that building.

So, through the persistence of “Indiana” Schmidt, and her search for the lost mural, Buck Winn’s “The History of Ranching” survives, and a major work by this noted artist can be enjoyed for generations to come.